Your Ultimate Guide to Kitchen Cabinet Door Materials in the UK (2025 Edition)

- Maayan Raviv

- Aug 7, 2025

- 18 min read

Updated: Aug 8, 2025

Planning a kitchen update? One of the most surprisingly tricky decisions you’ll face is choosing what your cupboard doors are made of. It might not sound glamorous, but behind every sleek, modern kitchen you see in magazines is a series of decisions about cost, durability, style, ease of maintenance—and increasingly, sustainability.

In recent years, kitchen door materials have gone through something of a revolution. Gone are the days when your only options were MDF wrapped in vinyl or plain gloss paint. In 2025, homeowners are spoilt for choice with an impressive range of finishes, colours, textures, and even high-tech innovations like thermal healing and anti-fingerprint surfaces.

Let’s take a tour through the most comprehensive guide to kitchen cupboard/cabinet door and drawer fronts materials in the UK today, looking not just at what they are, but how they perform and what kind of kitchen each one suits best. This information is relevant whether you ae looking to get flat packed, ready made or costume kitchen cabinets.

Let's begin: Background to kitchen cabinet guide - do not skip if you are new to this world of kitchen design.

The great majority of kitchens are made of MDF at the core, with different types of finishes. Some higher quality board/kitchen manufactureres use HDF, which is the same as MDF, but denser, stronger, harder and more resistant to moisture, which is why, if you can afford it, and you prefer the painted finish, I would reccomand spending the extra cash.

Many luxury kitchens are made of solid wood, but, it is the more expensive option, and not necessarily better. Wood can only be painted or lacquered, though I can't think of why someone would paint over solid wood that already has beautiful natural pattern, it is good to mention that paint on wood is more prone to tiny cracks as wood expends and shrinks with heat and humidity. For me, lacquered solid wood would be the only option I would consider. The main advantage of solid wood (other then just being gorgeous) is that it is highly durable, can be restored easily or can be have a new look with paint or different shade lacquer. The other time I would consider wood is if I'm going for the in-frame flat kitchen cabinets. You can get the in-frame profile, with shaker style doors and drawere fronts, with a combination of solid wood and MDF.

So back to MDF: MDF is made from resin and wax compressed wood fibres; it offers a smooth surface that's easy to laminate, veneer, paint or foil. It is short for Medium -Density Fibreboard. It's basically wood fibres, mostly sourced from carpenters and recycled and dense to make a board. It is smooth and consistent.

Some kitchen suppliers use chipboard as the base layer that's laminated with melamine, such as Ikea. Chipboard is more affordable then MDF, but also less durable and can highly vary in durability depending on the quality of the board. It is commonly used as the carcass of the kitchen.

MDF is also great for creating intricate profiles, bevels and grooves, that chipboard cannot do cleanly. It is laminated, veneered or painted for a nice finish. Because it is more expensive then chipboard, it is only used as carcass for high end kitchens, but it's really not necessary.

Gloss, Matt, and Everything In Between: Kitchen Cabinets Finishes Explained

Finishes define not just the look but also how your doors perform day to day. Here’s a closer look:

Melamine-faced chipboard (MFC) is common in budget kitchens. It comes in hundreds of colours and patterns but can feel a bit basic. On the other hand, high-pressure laminate (HPL) is thicker, more durable and found in mid- to high-end kitchens, especially those seeking scratch resistance.

Vinyl or foil-wrapped doors are budget-friendly and mimic more expensive finishes. However, they can peel over time—especially near heat sources.

Painted or lacquered MDF is a timeless mid-range choice, giving kitchens a smooth, customizable look. Choose matt lacquer for a muted effect, or gloss lacquer for a reflective, mirror-like finish often found in high-end German and Italian designs.

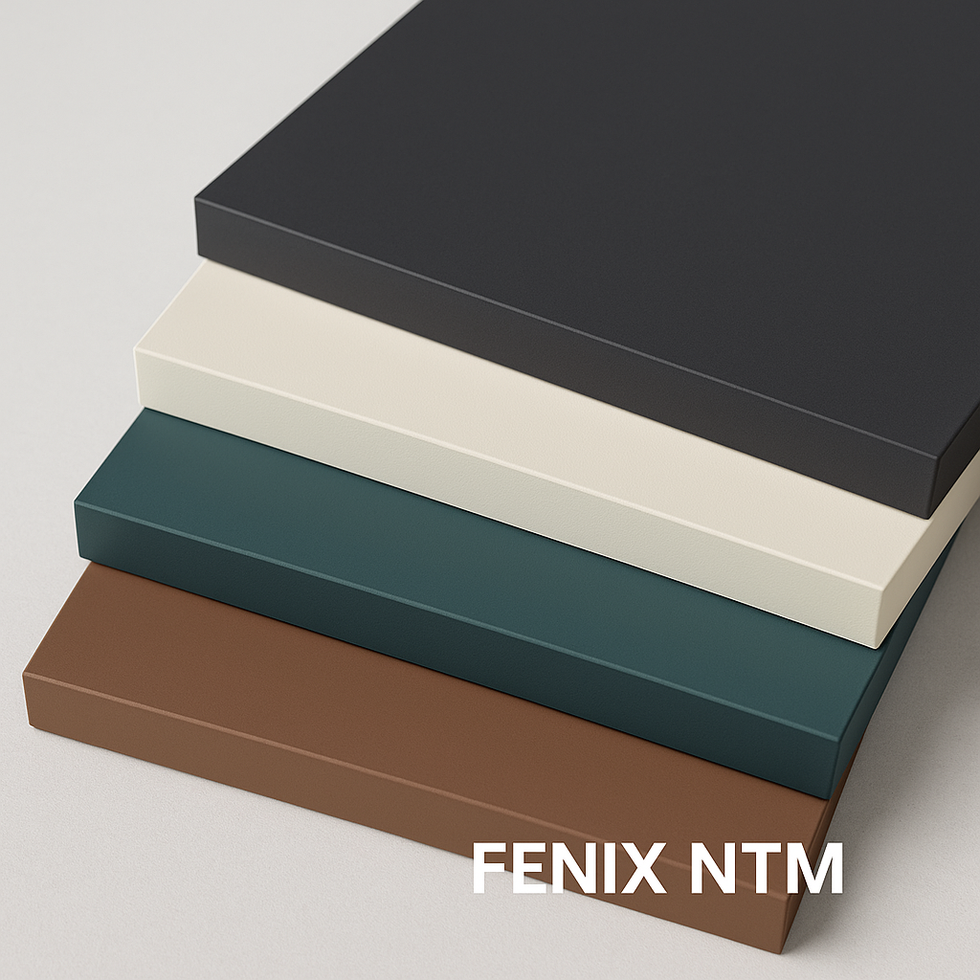

If you’re after cutting-edge performance and modern style, nanotech materials like FENIX NTM and PerfectSense Matt should be on your radar. These offer soft-touch, anti-fingerprint finishes that are a dream to clean and look stunning in contemporary settings.

Going Green: Natural, Reclaimed, and Engineered Wood Options

Natural materials bring character and warmth to kitchens. Solid wood—especially oak, ash, or walnut—remains a favourite for its grain and charm, though it requires a bit more care.

A more sustainable and trendy choice is plywood, especially birch or Douglas fir. It’s strong, stylish, and loved by designers for its Scandi aesthetic. Add a veneer or coloured oil stain, and you’ve got a durable, eco-conscious kitchen.

Bamboo is another hero of sustainable design. FSC-certified bamboo grows fast, needs no fertiliser, and captures more CO₂ than hardwoods. When treated properly, it’s just as tough as traditional options.

Reclaimed wood veneers offer a rustic, lived-in feel while ticking every box for eco-friendliness.

Industrial & High-Tech: Metal, Glass & Acrylic Kitchens

For ultra-modern homes, stainless steel or powder-coated mild steel doors offer unparalleled durability. They’re hygienic, non-porous, and immune to warping or cracking. Just note: they can feel cold, and fingerprints may be an issue unless you choose brushed or textured versions.

Glass fronts—whether glossy or frosted—create a sleek, reflective finish. They’re great for making small kitchens feel bigger but do show smudges. Meanwhile, acrylic doors, especially thick solid ones like Parapan®, deliver unmatched shine and colour intensity, though they’re harder to repair if scratched.

The Showstopper: Laminated Natural Stone Doors

One of the newest and most visually stunning options available in the UK is laminated stone. These doors feature a real natural stone veneer—like marble, travertine, or granite—bonded to lightweight core materials such as aluminium honeycomb, fibreglass, or even ultracompact ceramic.

Here’s why designers are embracing them:

Aesthetics: With real stone veining and seamless joints, these doors bring a luxury statement to any kitchen.

Strength-to-weight: Honeycomb cores reduce the panel weight by up to 80%, making installation and support easier.

Durability: Especially when using harder stones like granite or quartzite. Some panels even feature book-matched patterns for a seamless, artful appearance across multiple cabinet fronts.

But they’re not cheap. The materials and processes are sophisticated and price reflects it. Repairs can be tricky too. Still, for the right client, laminated stone offers a rare blend of beauty and performance.

Base Layer Materials and Construction for natural stone kitchen

Laminated stone panels use a variety of core backing materials. Key options include:

Aluminium Honeycomb: A common high-performance core comprising thin aluminum sheets and a hexagonal honeycomb structure. This core is exceptionally light yet stiff, reducing stone panel weight by ~80% versus solid slabs. In short, aluminium honeycomb cores provide excellent rigidity and low weight, though at high material cost.

Fiberglass Composite: Instead of metal, some panels use fiberglass-based cores. StoneSize’s SSHF line features a “fiberglass honeycomb”. Fiberglass (often glass-fiber reinforced polymer) cores are extremely strong and weather-stable Fiberglass cores can be even lighter than aluminum but may be somewhat thicker for equal stiffness. Cost is still high (composites and honeycombs are specialty materials), but they offer an alternative when metal is undesirable.

Ultracompact Ceramic (Porcelain) Backing: In this construction, a thin slab of sintered ceramic/porcelain is used as the backing instead of a honeycomb. This porcelain base is dense and non-porous so it prevents moisture transfer that could stain the stone. The trade-off is weight – porcelain has similar density to stone, However, the porcelain backing is relatively thin and cost-effective compared to honeycomb. This approach is useful when ultra-thin (~1 cm) panels are needed or for wet-area cabinetry where a non-absorptive core is critical.

Wood-Based Cores (MDF/Plywood): For certain interior applications, a traditional wood substrate can be used. This was used for kitchen worktops and could be adapted to thick cabinet door panels. The benefit is low material cost and easy joinery (wood edges can be shaped, and standard hinges or screws hold well). However, wood-backed stone panels are much heavier. Wood is also moisture-sensitive and requires a vapor barrier and sealing to prevent warping or delamination. Modern lightweight panel makers tend to avoid wood cores for doors, except in static pieces like countertops. Still, some custom fabricators may laminate stone to MDF for one-off cabinetry if weight is not a concern.

Other Core Materials: A few niche solutions exist. Carbon fibre sheets can reinforce stone, yielding very thin yet strong panels – though extremely expensive for cabinet use. There are also polymer or foam cores (e.g. polyurethane foam boards) occasionally used for DIY lightweight stone, but they lack the stiffness of honeycomb. Steel honeycomb is used in special fireproof panels but is heavier than aluminum. Generally, aluminum and fiberglass composites remain the preferred backing materials in the UK market for high-end stone cabinetry.

Stone Finishes and Veneer Thicknesses

One major appeal of these panels is the variety of natural stone finishes available. Nearly any stone slab can be sliced and laminated, so long as it can be cut to a few millimeters thick.

Typical veneer thickness for the stone layer ranges from ~3 mm to 7 mm, depending on the stone and application. Softer stones (marble, travertine) or those with more veining may be cut a bit thicker (5–7 mm) to reduce fragility, whereas very strong stones (granite, basalt) or uniform engineered stone can go as thin as ~3 mm. Some specialty products use even thinner sheets – for instance, “flexible stone veneer” sheets like Slate-Lite use ~1–2 mm slices of slate on a resin backing for wallcoverings, but for laminated doors and panels the minimum practical stone thickness is around 3 mm to ensure durability once bonded.

Surface finishes on the stone can be whatever one would apply to a full slab: polished glossy, honed (matte), leathered/textured, etc.

Manufacturing Process of Laminated Stone cabinets

This entire process is highly technical, and top manufacturers have refined it over decades. Grama Blend notes that turning slabs of heavy stone into “ultra-thin, large-format” panels is “an art [we] have perfected over the past 25 years”. The result is a panel that retains the natural beauty of stone but is “safe from breakage” during handling and use. Notably, by using large formats and tight joins, installers can create expanses of stone with virtually no visible seams, maintaining continuous patterns across cabinetry.

(Aside: A subtle point in manufacturing – to maximize yield, some companies laminate first and then slice the stone facing in the panel to create multiple doors with continuous grain. For instance, a large panel might be fabricated with bookmatched stone and then cut into several cabinet fronts that together show a flowing vein pattern.)

Contradictions/Notes: All sources agree on the basic lamination method, though marketing language differs. For example, StoneSize emphasizes their patented innovations (backing materials and processes) as part of TINO’s “constant spirit of innovation”, while Gramablend prides itself on being the “only true lightweight marble producer in today’s global market”– a bold claim given companies like StoneSize and others also produce similar panels. These statements reflect competitive branding rather than technical differences. Both firms essentially use comparable epoxy bonding and composite layering techniques (no major contradiction there).

Availability and Applications in the UK

In the UK market, lightweight stone panels are a niche but growing segment, primarily in high-end design and specialty projects. Grama Blend UK is a direct manufacturer/supplier with a base in Wokingham, serving both residential and commercial clients nationally

StoneSize panels, while produced in Spain, are available to UK projects through direct order or possibly via partner firms. StoneSize’s focus on facades and yachts suggests they have supplied UK or European superyacht builders and possibly some architectural projects. However, for kitchen-specific availability, StoneSize does not (as of latest info) have a UK showroom; a client or designer would typically contact them or their parent TINO for an international shipment. It’s worth noting there are also other UK-based firms offering similar products (e.g. StonePly and Starel Stones have UK distributors), so a savvy consumer might have multiple options beyond just Gramablend and StoneSize.

Performance Evaluation (Cost, Aesthetics, Durability, etc.)

Finally, we assess laminated stone cabinet doors across key performance metrics, with scores from 1–100 (higher is better) for an at-a-glance comparison:

Cost: 20/100 – Expensive. Laminated stone panels are a premium product, typically custom-made.

Aesthetics: 95/100 – Stunning, unparalleled. It’s hard to beat the visual impact of real natural stone surfaces.

Durability: 85/100 – Generally very durable, with some caveats. On one hand, the stone veneer itself, especially if using granite or quartzite, is extremely scratch and heat resistant – far more than painted or wood doors. There’s no worry about veneer peeling (the “veneer” is stone, not a printed film). The composite structure is engineered to be strong: these panels have high flexural strength and impact resistance relative to their weight. The reason I don’t score closer to 100 is the nature of some stones: Marble and travertine are softer and can scratch or chip at edges if banged hard. A dropped heavy pot could still chip a corner. Also, if a panel does get damaged, repair is not simple – a deep scratch or etch in the stone may need professional re-polishing or replacing the panel. The adhesive layer and bond have proven durable in long-term installations, but extreme heat or water ingress over many years could potentially degrade bonds if not properly sealed (this is rare and panels are tested for thermal cycling). Overall, these panels are at least as durable as natural stone countertops – meaning they’ll last decades with basic care. They won’t corrode or warp. The backing materials (aluminum, fiberglass, porcelain) are all inherently rot-proof and stable. So, high marks for longevity and robustness, especially if harder stones are used for high-traffic areas.

Ease of Cleaning: 75/100 – Moderately easy. The stone surfaces are generally easy to wipe clean with a damp cloth and mild cleaner, much like a stone countertop. A polished granite or quartzite door is essentially a smooth, non-porous surface (once sealed) so it won’t trap grime and can be cleaned with standard kitchen sprays, so it depends on the stone: Granites and engineered quartz surfaces are nearly impervious and can be cleaned aggressively without issue – those would score ~90/100. Marble/limestone surfaces are a bit more delicate – acidic spills (lemon juice, vinegar) could etch the finish if not quickly wiped, so users must be mindful (this is the same issue with marble counters). The composite edges, if exposed (like a honeycomb edge), could collect dust, but typically edges are sealed or covered. On balance, cleaning is comparable to other high-end finishes and generally straightforward, but the need for proper stone care (pH-neutral cleaners, periodic sealing of certain stones) means it’s not completely maintenance-free.

Sustainability: 60/100 – Mixed sustainability profile. There are both positive and negative aspects here. On the plus side, using a thin stone veneer means maximizing the yield from quarried stone; you can cover more area with less raw stone, potentially reducing quarrying impact. The lighter weight also leads to lower shipping emissions (more panels per truck, less fuel per square meter of stone transported) and can enable use of stone in retrofits without requiring new structural supports. Additionally, many honeycomb panels (especially aluminum ones) are fully recyclable at end-of-life – the aluminum, stone, and fiberglass can theoretically be separated and recycled, though in practice this may be difficult. Now the downsides: The production of aluminum, porcelain, and epoxies is quite energy-intensive and has a significant carbon footprint. For example, aluminum honeycomb is an energy-heavy material, albeit one that saves weight later. The epoxy adhesives and any fiberglass are petroleum-based and not biodegradable. At end of life, if not carefully disassembled, a composite panel might end up in landfill since it’s not easy to recycle a bonded stone/aluminum sandwich without processing. Compared to a solid wood door (which is relatively low-impact and renewable), these panels fare worse environmentally. That said, some manufacturers are moving toward greener practices – e.g. using recycled aluminum content in honeycombs, and the fact that these panels allow stone to be used in ways that might avoid more pollutive materials. Gramablend’s new Ecoline product line (as the name implies) might be addressing some sustainability concerns, perhaps using low-VOC adhesives or standardized cores for recyclability (their 2024/25 Ecoline release suggests an aim for more eco-friendly elevator panels). Overall, while the stone itself is natural, the composite nature reduces the sustainability score. A 60/100 reflects that it’s neither terrible nor truly green – it’s an upscale product with some resource intensity. Clients opting for this are usually prioritizing the longevity and luxury aspects over strict eco-friendliness.

In summary, laminated stone cabinet doors excel in aesthetics and unique performance (lightweight strength), while being most challenged in cost and to a lesser extent maintenance. The above scores assume a well-constructed panel by a reputable manufacturer

Print-Friendly Guide: At-a-Glance Comparison of All UK Kitchen Cabinet Door Materials:

Material/Finish | Description | Availability and Notes |

|---|---|---|

Solid wood (painted or stained) | Natural hardwood kitchen cabinets (oak, maple, ash) are considered top‑end; they use traditional joinery and are durable and sustainable but require regular maintenance and may warp if exposed to moisture. Only option for in‑frame doors. | Available from bespoke joiners, Howdens and German brands such as Bauformat and Nobilia (premium ranges). Generally made-to-order; can be painted, stained or clear‑lacquered. |

MDF/HDF (painted or lacquered) | MDF is made from resin‑ and wax‑compressed wood fibres; it offers a smooth surface for painting or spray lacquering. Painted MDF is more durable than foil-wrapped doors because it resists peeling in heat/humidity. HDF is similar or MDF only more dense and durable then MDF. | Widely available from UK suppliers (Howdens, Wren, Magnet). High‑gloss or matt lacquer finishes (e.g., PerfectSense matt boards) are created by repeatedly spraying lacquer onto an MDF core. Matt lacquered doors can be fully lacquered or lacquered on the face and edged. |

Melamine‑faced chipboard (MFC/low‑pressure laminate) | A particleboard core is faced with melamine to create an affordable and durable door. Good‑quality MFC is water‑resistant and scratch‑proof, but low‑quality boards can swell or sag when moisture penetrates. | MFC doors are the cheapest option and are used in flat‑pack kitchens (B&Q, IKEA). They come in many colours/patterns but have visible edges. |

High‑pressure laminate (HPL) | HPL uses thicker laminate (~0.7 mm vs H0.1 mm for MFC), giving a more durable, scratch‑resistant surface and greater heat/water resistance; it is more expensive. Used for flat doors individually edged on all four sides and finished with a 1 mm laminate coating. Can be laminated on chipboard or MDF as base layer. Note that Edging can be done with various materials. | Supplied by brands such as Duropal, Kronospan and Egger. Doors are typically edged with ABS or laser‑edge. Super‑matt HPL variants (e.g., XTreme Matt by Pfleiderer) incorporate anti‑finger‑print coatings. |

Super‑matt nanotech laminate (FENIX NTM/Bloom) | Fenix NTM is a laminated material produced by Arpa Industriale. It has a nanostructured matt surface which is anti‑finger‑print, soft to the touch, water‑repellent, heat‑ and impact‑resistant; superficial micro‑scratches can be “healed” with heat. Fenix NTM Bloom replaces 50 % of phenol resin with lignin, reducing CO₂ by up to 26 %. | Sold in the UK by Plykea, Reform, Custom Fronts and other bespoke companies. Usually bonded to an FSC‑certified birch plywood core. |

Anti‑finger‑print lacquer (e.g., German “anti‑finger‑print” doors) | Matt lacquer doors with an innovative lacquering process that prevents marks and fingerprints. Fewer colours are available and they are more expensive but provide low‑maintenance surfaces. | Offered by German manufacturers such as Bauformat and Nobilia. Suitable for high‑traffic kitchens in dark colours. |

PerfectSense® premium lacquered boards | Egger’s PerfectSense portfolio uses Premium Gloss boards with a mirror‑like lacquer finish; rooms look larger due to the reflective surface. Premium Matt boards have a velvety‑smooth surface with anti‑finger‑print and scratch‑resistant properties. | Available via UK suppliers such as HPP and Lawcris. Boards are lacquered on a MDF core and come in various colours. |

Vinyl/foil wrap (PVC‑wrapped doors) | Adhesive PVC vinyl is vacuum‑formed over a pre‑machined composite wood substrate; this creates a glossy or matt surface. High‑quality foil wrapping uses heat‑pressed adhesives to prevent delamination. Vinyl wrap doors are cost‑effective, available in many colours, easy to clean and sustainable by extending the life of existing cabinetry. However, the edges can peel or bubble over time and the surface is sensitive to heat. | Supplied by budget ranges (B&Q, Wickes) and by specialist companies (Lark & Larks, Happy Doors) for door replacement. |

Acrylic (solid and acrylic‑faced) | Solid acrylic doors (e.g., Parapan®) consist of 18 mm thick acrylic and produce a deep, mirror‑like gloss finish; they are hard‑wearing, stain‑resistant and non‑porous. Acrylic‑faced doors are cheaper; a thin sheet of acrylic is bonded to MDF and edge‑sealed, but they are softer and prone to damage. Acrylic provides the highest gloss but scratches cannot be repaired and colour matching is difficult when replacing doors. | Available from premium door suppliers (e.g., Parapan, Acrylic Couture) and online retailers. Typically used in contemporary high‑gloss kitchens. |

Gloss lacquered MDF | A repeated spray‑lacquer process over a primed MDF core builds a deep, even high‑gloss coating. The jointless lacquering is highly resistant to moisture and chemicals and withstands wear and tear. It is labour‑intensive and more expensive than laminate or foil, but provides a durable, consistent mirror finish. | Offered by German and Italian brands (Bauformat, Alno, Luce, etc.). Doors can have laser‑fused edges for a seamless appearance. |

Matt laminate (MFC or HPL) | The least expensive matt option uses MFC; a better‑quality option uses HPL, with individually edged doors and a 1 mm laminate coating. Matt laminates are available in the widest choice of colours, are hard‑wearing and easy to clean. | Available from mainstream kitchen companies (Howdens, Wren, IKEA) and from German manufacturers (Nobilia). |

Plywood with veneer | Plywood is made by bonding multiple wood layers with glue, creating a strong, stable and moisture‑resistant panel. Birch or poplar ply resists warping and is considered more sustainable due to lower formaldehyde emissions. Plywood doors are often veneered with wood or laminates. | Used by companies like Plykea, Custom Fronts and Superfront for IKEA door fronts. Edges are usually sealed with oil and need periodic treatment. |

Reclaimed/engineered wood | Thin layers of reclaimed wood are pressed onto plywood for stability, giving character and sustainability. The surface can be uneven and prone to warping; doors are expensive due to re‑processing. | Offered by bespoke makers (Smile Kitchens, Woodface) for eco‑conscious clients. Often finished with clear lacquer or oil. |

Bamboo | Sustainable bamboo kitchen doors (e.g., from Custom Fronts) are handcrafted in the UK. Bamboo is CO₂‑negative, incredibly durable and low‑maintenance. It is available in smoke, warm and natural finishes and blends Japanese and Scandinavian aesthetics. Bamboo grows rapidly, captures 70 % more carbon than hardwood and is grown without fertilisers. | Sold by Custom Fronts, Noremax and Ask og Eng; these fronts fit IKEA or bespoke carcasses. Bamboo panels are either solid laminated bamboo or engineered veneer. |

Glass | Gloss glass doors use toughened safety glass bonded to an aluminium or MDF frame. They have a mirror‑like, highly reflective surface and are scratch‑resistant and durable. There are some stunning metallic and marble-like colours available for a unique wow factor. | Offered by premium manufacturers (Bauformat, Brigitte). Options include clear, frosted, ribbed and leaded glass. |

Powder‑coated mild steel | Powder‑coated mild‑steel cabinets combine durability and aesthetics. Polyester powder‑coated doors provide strength, cleanliness and a wide range of colours; they are more appealing than bare stainless steel. The satin gloss finish hides fingerprints and dirt better than high‑gloss and requires little maintenance. Avoid abrasive cleaners; mild detergent is recommended. | Used by commercial‑kitchen manufacturers such as Steelplan Kitchens and Danver. Doors are made from mild steel panels coated with polyester powder. |

Laminated natural stone | Consist of a thin real-stone veneer bonded to a lightweight backing. This composite construction yields panels that look and feel like solid stone but at a fraction of the weight. There are many options available in terms of backing and veneer material, that deserves its' own section below to learn more. Though I must warn you, the price is not for the faint hearted. | Offered by brands like Bauformat, Leicht and Porcelanosa (ceramic‑fronted doors). Ceramic fronts are usually thin porcelain laminated onto aluminium or MDF. |

Kitchen Cabinet Material Comparison Table (UK 2025): Costs, Durability, Sustainability & More

To help you compare options, each material/finish is scored out of 100 for cost (lower score = cheaper), aesthetics (appearance and visual impact), durability (resistance to wear, heat and moisture), ease of cleaning (tendency to show marks and required maintenance) and sustainability (renewability, recyclability and emissions). These scores are relative and subjective but based on the evidence above.

Terminology

MDF (medium‑density fibreboard) – wood fibres bonded with resin and wax under heat and pressure; provides a smooth surface.

MFC (melamine‑faced chipboard) – particleboard faced with a thin melamine sheet (low‑pressure laminate). Uses less material than HPL but is less resistant to moisture.

HPL (high‑pressure laminate) – kraft paper impregnated with phenolic resin and bonded under high pressure and heat; thicker and more durable than melamin. HPL doors are edged and finished with a 1 mm laminate coating

Lacquer (paint) – several layers of primer and lacquer sprayed onto an MDF or wood substrate. Gloss lacquer involves multiple coats and polishing to create a mirror‑like surface, whereas matt lacquer uses fewer pigments and can incorporate anti‑finger‑print technology

Vinyl/foil wrap – PVC film heated and vacuum‑formed over a routed MDF or composite door. Adhesive (PUR hot‑melt) prevents delamination. Prone to peeling around heat sources.

Acrylic – solid acrylic or acrylic‑faced boards provide a high‑gloss, colour‑rich surface. Solid acrylic (e.g., Parapan®) is a thick plastic sheet; acrylic‑faced doors bond a thin acrylic skin to MDF

Nanotech laminate (FENIX NTM) – multiple layers of paper impregnated with resin and topped with nanoparticles; cured via electron beam. The nanostructure gives anti‑finger‑print, soft‑touch and self‑healing properties

PerfectSense® – Egger’s range of lacquered MDF boards with a velvety matt or mirror‑like gloss finish. The matt version uses a high‑quality lacquer that provides anti‑finger‑print properties

Birch plywood – multiple layers of birch veneer bonded with low‑emission glue, providing strength and moisture resistance. Edges need sealing to prevent water ingress.

Powder‑coated mild steel – mild‑steel panels coated with polyester powder and baked. Provides a coloured, satin finish that hides fingerprints and resists corrosion

Toughened glass – glass heated and rapidly cooled to increase strength. Used in gloss glass doors for a mirrored finish

In-frame kitchen design - framed doors with inset panels & exposed hinges for a classic look.

Veneer - A thin layer of real wood

Contradictions & considerations

Durability of vinyl wrapping – Some sources describe vinyl wrap as durable and long‑lasting (5‑10 years) with easy cleaning, while others highlight the risk of peeling edges and heat sensitivity. The quality of the vinyl and installation method largely determine longevity.

Acrylic vs lacquered gloss – Acrylic doors provide a superior mirror finish but are more expensive and cannot be repaired when scratched Gloss lacquered doors are cheaper and can be repaired but are slightly less durable and may chip

Textured finishes – Textured metal or powder‑coated doors are described as easy to wipe down and hide fingerprints, yet powder‑coated mild steel still requires gentle cleaning with mild detergent to avoid damage.

Stainless steel aesthetics – Stainless steel is praised for its durability and hygiene but criticised for its cold, industrial appearance and susceptibility to fingerprint. Powder‑coated steel offers a warmer aesthetic but also needs careful cleaning.

Summary

Selecting a kitchen cupboard door material involves balancing budget, aesthetics, durability, maintenance and environmental impact. Budget‑friendly options like MFC and vinyl wrap offer wide colour choices but trade off durability and sustainability. Premium finishes such as gloss or matt lacquer, Fenix NTM, PerfectSense® or high‑pressure laminate provide improved durability, anti‑finger‑print properties and refined aesthetics at a higher cost. Natural materials—solid wood, plywood or bamboo—deliver warmth and sustainability but often require more maintenance and have higher price points. Metal options (stainless steel, powder‑coated steel) and glass provide contemporary looks and durability but show fingerprints and cost more. Understanding these trade‑offs allows you to choose finishes that suit their style, lifestyle and environmental values.

Whatever your budget or aesthetic, there’s never been a better time to design a kitchen that looks great and works even better. If you’re curious about specific combinations, colour schemes, or where to see these materials in person, drop an email and I’ll point you in the right direction.

Happy designing!

Comments